The Genius of Electricity(“Golden Boy”) Trademark of Western Electric.

Renamed “The Spirit of Communications” by the local Bell operating companies.

See photos of statue and details at end of this document.

Click here get a larger view of this chart.

We Offer Personalized One-On-One Service!

Call Us Today at (651) 787-DIAL (3425)

Click image above to see enlarged view

Contents:

-

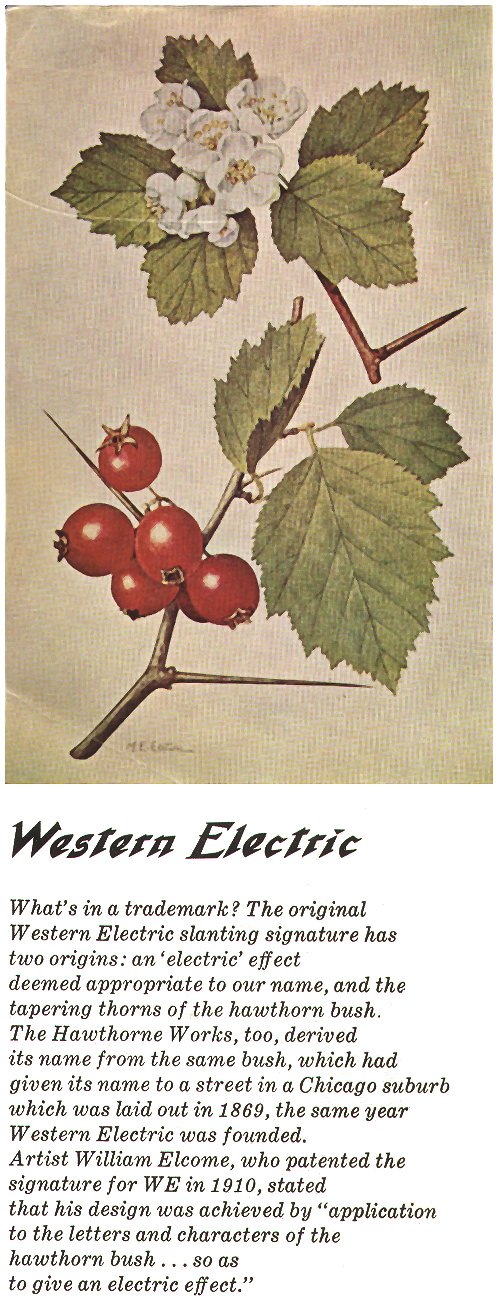

Western Electric logo - From www.westernelectric.com website

-

Reader’s Digest story Mama Visits the Factory

-

Book review of Manufacturing the Future

-

Western Electric Stock Certificate - Contributed by Robert P Mohalley

Western Electric - A Brief History

Download the Microsoft Word 97 format of the following document by clicking here.

An old Western Electric hand once said: “I always like to think of AT&T as a manufacturing company that happens to have a few operating departments.” As that manufacturing company, now called Lucent Technologies, casts loose the last of its operating departments, it arrives at an old place - that of an independent company-at a new time. More than a century ago, prior to joining the Bell System, Western Electric was the largest electrical manufacturer in the United States. Now, as an independent $20 billion company, Lucent Technologies will easily break into the ranks of the Fortune 50. Just as Western Electric of the late 1870s was both a distributor of telephone equipment for the new Bell company and a supplier to Bell’s primary communications competitor (Western Union), Lucent Technologies will manufacture both for AT&T and the regional telephone companies.

To succeed as a telecommunications manufacturer today requires constant innovation, one of Western Electric’s perpetual hallmarks. At its 1869 inception, the company provided parts and models for inventors, such as co-founder Elisha Gray. In the early 20th century, when a handful of companies assembled scientific researchers to expand their innovative capacities, Western Electric did so in a big way. The research branch of Western Electric’s engineering department became Bell Laboratories, the greatest private research organization in the world- and an integral part of the new Lucent Technologies.

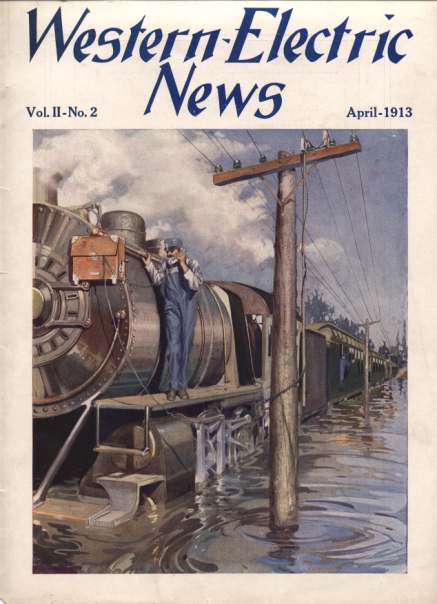

Along the way, the company made tremendous breakthroughs. In 1913, Western Electric developed the high vacuum tube, thereby ushering in the electronic age. The company subsequently invented the loudspeaker, successfully brought sound to motion pictures, and introduced systems of mobile communications which culminated in the cellular telephone.

Another requisite “core competency: for success in manufacturing is corporate concern for quality. Today’s “total quality” movement can be trace to the work of three individuals- Walter Shewhart, W. Edwards Deming, and Joseph Juran-who got their start at Western Electric, then introduced their idea to the Japanese after World War II. Bonnie small then brought quality expertise to the shop floor in 1958 with the “Western Electric Statistical Quality Control Handbook,” which is still the world’s shop floor bible of quality. The company practiced what it preached: In 1992, AT&T Transmission Systems won a Malcolm Baldrige Quality Award, and in 1994 AT&T Power Systems became the first U.S. manufacturer to win Japan’s Deming Prize for Total Quality Management.

Lucent Technologies’s consumer products line renews a Western Electric tradition. In its early days, Western Electric made communications equipment and other electrical devices- including alarms. Western Electric later carried on an extensive line of household appliances, from sewing machines to vacuum cleaners, until selling off its consumer goods segment in the 1920s, After a long absence, Western Electric returned to consumer markets in the 1970s through its offerings in Phone Center Stores. Lucent Technologies now sells phones, answering machines and other electrical devices-including alarms.

By competing in international markets, Lucent Technologies travels another path once trod by Western Electric. In 1882, the year it joined the Bell System, Western Electric subsequently manufactured in every country with significant telephone systems, until spinning off its international operations in 1925, and its Canadian manufacturing holdings after 1956. Consequently, Lucent Technologies competitors such as Alcatel N.V., Northern Telecom and NEC all share Western Electric roots.

Gray and Barton

Lucent Technologies is a manufacturing company that is actually older than its onetime “parent.” Western Electric did not spring from the brow of Bell Telephone, but existed before Alexander Graham Bell made his invention. Before Bell came along, Western Electric was the principal manufacturer for Western Union, the telegraph company. Bell’s subsequent acquisition of Western Electric was crucial in the establishment of a nationwide phone system, a system characterized by its early, primary emphasis on the production and distribution of hardware.

In the 1980’s, Victor Kiam became one of the most recognized executives in corporate America through a series of advertisements in which he explained his purchase of the Remington Company as the act of an extremely satisfied customer. More than a century earlier, former Oberlin College physics professor Elisha Gray made a similar testimonial on behalf of a tiny Cleveland manufacturer of fire and burglar alarms, and other electrical devices, on which he relied for parts and models for his various experiments. Professor Gray had previously offered to go into business with one of the company’s two owners, but George Shawk had recoiled from the proposition because “Gray would want to put every man in the shop into his darned inventions.” That is just what Shawk’s partner, Enos Barton–who recognized the market potential of Gray’s inventions–wanted. Barton encouraged Gray to buy Shawk’s interest, so the company’s best customer became half-owner. Enos Barton’s recognition of the value of Elisha Gray’s inventions began a tradition of manufacturing innovation that characterized its subsequent life as the Western Electric Company, and is sustained in Lucent Technologies today.

Gray and Barton’s company had roots in the telegraph business. In 1856, twelve years after Samuel F.B. Morse opened his first telegraph system, various scattered telegraph companies consolidated into the Western Union Company. The various manufacturing shops associated with those telegraph companies were also consolidated into two shops, one at Cleveland, Ohio, the other one in Ottawa, Illinois. George Shawk purchased the Cleveland shop, which made working models of inventions, and manufactured telegraph instruments. Enos Barton, who had been chief telegraph operator for Western Union at Rochester, New York, became Shawk’s partner for a brief period in 1869, until Gray bought out Shawk.

Later that year, Western Union general superintendent General Anson Stager became a third partner with Gray and Barton, and convinced them to move the shop to Chicago. Stager’s career in telegraph had already spanned more than two decades, beginning in 1846 as a telegraph operator in Philadelphia. In the early 1850’s, he helped organize some telegraph lines, which later became part of Western Union. During the Civil War, Stager served General George McClellan as Chief of United States Military Telegraph.

In 1872, Stager convinced his boss, Western Union president William Orton, to invest in the Chicago manufacturing enterprise. Gray and Barton reorganized as the Western Electric Manufacturing Company, a company with strong ties to Western Union. Three of the company’s five directors were also directors of Western Union. Furthermore, one-third of the capital for the newly named Western Electric Company came from Western Union’s William Orton; one-third came from Western Union’s Anson Stager; and the remainder came from Gray, Barton and their employees. Western Union further demonstrated its commitment to Western Electric by closing its Ottawa plant in the expectation that Western’s Chicago plant would meet most of its needs for telegraph equipment.

The mid-1870’s were a heady time for Western Union. The well capitalized giant had established a network of wires and offices connecting every city or town of consequence from coast to coast. Even before the 1869 completion of the transcontinental railroad, Western Union had emerged as America’s only truly nationwide company, and was poised to reap the fruits of a monopoly on transmission of news to America’s newspapers. As Western Union’s principal supplier, Western Electric also seemed positioned to capitalize on the telegraph’s position on the cutting edge of communications–until 1876.

Western Electric gained prestige at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, when its products won five gold medals. In addition to telegraph equipment, the company offered a variety of electrical products, including various forms of alarms and mimeograph pens. The most significant product to the company’s future, however, was one unveiled at the Exposition in June by Alexander Graham Bell: the telephone. On February 14, Bell had sent one of his financial backers, Boston lawyer Gardiner Hubbard, to file a patent for his new telephonic device. Hubbard arrived at the U.S. patent office only hours before Bell’s closest competitor: Elisha Gray, who had sold his interest in Western Electric in 1875 and retired from the business.

Less than a year after the cash-strapped Bell’s patent was approved, Hubbard offered to sell the telephone patent to Western Union for one hundred thousand dollars–and Orton turned him down because he saw little future for the telephone. A year later, Orton changed his mind, and Western Union established the American Speaking Telephone Co., and Western Electric agreed to manufacture telephones for the new company. Western Electric brought divided allegiances to that arrangement because they had already become a distributor of telephone equipment for Bell. For some time, Western Electric straddled the fence, acting as distributor for Bell and as captive supplier to its only competitor. Western Union finally won undivided allegiance–just as a battle for control of the telephone erupted between the deep pockets of Western Union and the thinly capitalized Bell.

The battle lasted just over a year. Its brief duration was not a surprise; the outcome, however, was. The upstart Bell won. How did David slay Goliath this time? Bell’s principal ammunition was his 1876 patent. In September 1878, Bell Telephone Co. sued to protect Alexander Graham Bell’s patents from infringement by Western Union; by June 1879, testimony in the patent suit was complete, and it did not look good for Western Union. Five months later, Western Union abandoned the field. Western Union also faced attack from another front.

In the late nineteenth century, a laissez-faire environment nurtured industrial concentration in the United States. The result was the rise of a few powerful captains of industry, whose Olympian battles shaped the economic landscape below. One such battle pitted Titan against Titan for control of Bell’s antagonist. Angling to take over Western Union from William Vanderbilt, Jay Gould started the American Union Telegraph Company, in the hopes that the competition would reduce the value of Western Union stock. At the same time, Gould approached Bell general manager Theodore Vail with the intent of combining interests. Months later came what the Federal Communications Commission later called the “surprising capitulation of the powerful Western Union to the diminutive Bell Company.”

Although Western Union was frightened by the proposed Gould/Bell alliance, its greatest concern was threats to its core telegraph business. Western Union abandoned telephone rights and patents to Bell. In exchange, Bell agreed to transfer all telegraph messages to Western Union, to pay a 20 percent royalty on any telephone rental income they received in the United States for the next seventeen years, and not to use the telephone business for “transmission of general business messages, market quotations, or news for sale or publication in competition with the business of Western Union.” Gould finally wrested control of Western Union from Vanderbilt in 1882; by then, Western Union’s onetime supplier/owner had entered into an agreement to manufacture for the American Bell Telephone Company.

When individuals such as Victor Kiam and Elisha Gray purchase a company of which they are loyal customers, it is considered a testimonial. When a corporation purchases a supplier, it is called backward integration–and that is what Bell Telephone did with Western Electric. The company Western Electric hooked up with in 1881 was already substantially different from the original Bell Telephone Company. None of the four men responsible for the company’s founding– Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Watson, Gardiner Hubbard, and Thomas Sanders– played any technical or administrative role in the American Bell Telephone Company.

Western Electric joined the Bell system in 1881, when Bell purchased a controlling interest in its stock. Prior to that time, manufacture of telephones for the Bell system had undergone two phases. Beginning in 1877, it had been done in Charles Williams, Jr’s Boston shop, which had been the site of Bell’s early experiments. Within two years, increasing volume overwhelmed the Williams shop, and Bell had licensed additional manufacturers in Baltimore, Chicago, and Cincinnati. This interim arrangement solved Bell’s difficulties in meeting demand promptly, but the licensees were difficult to control. That led Bell to search for a single manufacturer with the resources to handle large volume. Bell found it in Western Electric, which by then was the largest electrical manufacturer in the United States.

In 1882, Western Electric and Bell signed an agreement that made Western Electric Bell’s exclusive manufacturer of telephones in the United States, while Western agreed to sell only to the American Bell Telephone Company (which in 1899 became AT&T), which then leased the phones to regional “operating” companies, who in turn leased the phones to end users. Those two contracts combined with AT&T’s agreements with its licensees to form the three pillars of the nascent Bell System, and provided the system’s organizing principle for the next century: long distance service–inaugurated in 1881 between Boston and Providence–was handled by the parent company, local service by the operating companies, and manufacture by Western Electric.

Research and the Bell System

The three contracts alone would have meant little without a source of innovation for the development of new products and the improvement of existing ones–especially after Bell’s patent expired. There were two directions Bell could go for technical innovation after 1894: to depend on outside inventors for innovation by purchasing their patents, or establish an in-house research organization to cultivate invention. A 1906 memo from AT&T’s chief engineer to the president of the company shows the direction in which Bell initially moved: “Every effort in the Department is being executed toward perfecting the engineering methods. No one is employed who, as an inventor, is capable of originating new apparatus of novel design. In consequence of this it will be necessary in many cases to depend on the acquisition of inventions of outside men.” One such man was a Columbia University electrical engineering professor named Michael Pupin.

Pupin was the archetypal independent inventor, even down to the eureka moment he experienced mountain climbing in Switzerland. Pupin had envisioned the loading coil, a method of amplifying the voice by long-distance telephone. Pupin’s idea became the single most important telephone-related invention between 1876 and 1913. Pupin sold the patent to AT&T in 1900. Meanwhile, the Western Electric engineering department concentrated on improvement and adaptation rather than creation.

That changed in 1907 when, during a financial panic, a syndicate of bankers took over AT&T and convinced Theodore Vail–company president in the mid-1880’s–to return. Vail, in turn, chose John J. Carty as chief engineer. Carty had been one of Bell’s original operators in the late 1870’s, before women replaced the teenaged boys. In 1881, Carty had demonstrated the advantage of two-wire telephone circuits, and subsequently acquired two dozen telephone patents. Carty became head of Western Electric’s Cable Department, and chief engineer of the long distance company. Now, the self-educated Carty championed of the idea of the company assembling scientists to perform research, rather than relying exclusively on outsiders.

Carty’s assistant, Frank Jewett, who had a doctorate in physics from the University of Chicago, was in a better position than Carty to recruit top university talent. When Robert Millikan, America’s foremost physicist, began sending Chicago’s top students to Jewett, including Harold D. Arnold, Western Electric’s engineering department developed a new “research branch.” The Research Branch grew from Arnold and his handful of assistants in 1911 to more than one hundred by 1916–at a time when business conditions forced the company to cut back in other engineering departments. Thus was born the organization that would become Bell Laboratories, the greatest corporate research organization in the world.

Transcontinental Telephone Line

Motivation thrives on striving for a goal that appears attainable only with a superhuman effort. Such efforts, when they succeed, are called “miracles”; examples include Dr. Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine, and John F. Kennedy’s promise to put a man on the moon before the 1960’s were over. During its formative years, Western Electric made just such a superhuman effort to meet the challenge of providing AT&T with the ability to offer transcontinental telephone service to coincide with the expected completion of the Panama Canal. The company’s efforts towards that end would make an impact beyond the immediate goal, ultimately transforming the face of many industries.

In 1909, on a visit to the West Coast, John Carty promised to make available transcontinental telephone service in time for the scheduled 1914 opening of the Panama Canal. To that point, the major breakthrough in long-distance telephone had been the introduction of loading coils, which reduced the tendency of a signal to grow weaker the longer the line over which it was transmitted. The use of loading coils in the absence of further technological advance was about to reach its limit: service from New York to Denver. Longer distance calling would require technology that had not yet been developed.

In 1912, Dr. Lee DeForest provided that technology, developing the audion, a three-element vacuum tube that could not only send radio waves more effectively than existing devices, but could amplify them. Western Electric’s Dr. Harold Arnold , who had the training in electron physics DeForest lacked, quickly grasped scientifically how the audion worked. Arnold thus knew how to turn it into a practical electrical amplifier, which is what Carty knew was needed. The result was development of a “high-vacuum tube” for amplifying sound in telephone cables in April 1913–and AT&T’s purchase of the audion patent from DeForest. The new tube allowed Western Electric to span the continent in 1913 and 1914. The circuit was successfully completed in June 1914, and successfully tested on July 29. Carty’s challenge had been met.

The planners of the Panama Pacific Exposition were less fortunate; the opening was postponed until 1915. Therefore, after hurrying for five years, AT&T had to wait six months to demonstrate its breakthrough. It was worth the wait: on January 25, 1915, 39 years after the first telephone conversation, the original participants reprised their roles: Alexander Graham Bell, from New York, called his associate Thomas Watson, who sat in San Francisco. After some initial pleasantries, Bell said, “I have been asked to say to you the words you understood over the telephone and through the old instrument, ‘Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.”’ From across the continent, Watson reminded Bell, “It would take me a week to get there now!” It would not take another 39 years to reach Europe. By 1927, a Western Electric radio-telephone link-up from New York to London established transatlantic service.

Loudspeakers

As so often happens, a technological breakthrough in one area had a wide-ranging impact in others. Development of the high-vacuum tube amplifier did more than make possible the first transcontinental telephone line. It revolutionized communications, leading to creation of new industries including radio, television, and sound motion pictures. In a sense, Arnold’s breakthrough marked the beginning of a new electronic age. Among the most immediate results of Arnold’s breakthrough was the development of public address systems. The high-vacuum tube made possible development of the “loud-speaking telephone” (or loudspeaker), allowing many people to hear what conventional telephone receivers had limited to an audience of one. Further developments in the loudspeaker made possible its use in large crowds, at stadiums or in convention halls. Indeed, Western Electric public address systems were used at the 1920 presidential conventions, and at Warren Harding’s 1921 inauguration. On Armistice Day (November 11) that year, Harding dedicated the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arlington National Cemetery. His address was sent by telephone lines to New York, and cross-country to San Francisco. In both cities, loudspeaker systems broadcast Harding’s speech. In 1924, nearly 40,000 people attended dedication ceremonies for the first public address system ever installed at a manufacturing facility. The site was Western Electric’s enormous Hawthorne plant near Chicago, where employees enjoyed the benefit of a system they had helped design and build.

The Hawthorne Plant

Western Electric founder Enos Barton, still president of the company in 1905, was responsible for moving the company’s main manufacturing plant that year from downtown Chicago to a more rural setting on the outskirts of the city. Barton’s urban-to-rural move contrasts with his move 36 years earlier, when he mortgaged the family farm in Jefferson County, New York, to raise money for his original investment in his Cleveland based partnership with George Shawk.

The rural Hawthorne plant became a virtually self-sufficient city, with a power plant, hospital, fire brigade, laundry, greenhouse, a brass band, and an annual beauty pageant. Hawthorne boasted a staff of trained nurses–who made house calls! Hawthorne absorbed the operations of the company’s existing plants in New York and Chicago and by 1914 it was Western Electric’s only manufacturing facility. During the next seven decades, the Hawthorne works–including more than 100 buildings–would produce telephones, cable and every major telephone switching system plus the equipment necessary to make it work. Western Electric even owned and operated the Manufacturer’s Junction Railway at Hawthorne, “the biggest little railway in the world,” which transported raw materials and completed cable around the plant. Hawthorne was also the cradle of industrial psychology, with a series of experiments that began in 1924. [Sidebar #2–Hawthorne Experiments]

1925 Restructuring

Besides acting as purchaser and as manufacturer for the Bell System, Western Electric also supplied its parent with executive talent. AT&T presidents from Harry B. Thayer to Frederick Kappel to Haakon Romnes each served as Western Electric president beforehand. The AT&T executive who presided over the biggest changes in Western Electric, and who served longest as AT&T president, Walter Gifford, started at Western but never became its president. Gifford began at Western in 1904 in the Chicago payroll department. By the time Gifford moved on to AT&T in 1908, he had become an Assistant Secretary at Western Electric.

The year Gifford ascended to the presidency of AT&T, he redirected the business of Western Electric: he established Bell Laboratories as a separate entity, set up a separate corporation for the company’s supply business. and sold the international business. Gifford established the separate entity called the Bell Telephone Laboratories Inc., which took over work previously conducted by the research division of Western Electric’s engineering department. Bell Labs was 50 percent owned by Western Electric, and 50 percent owned by AT&T. Nine years later, AT&T’s development and research group also joined Bell Labs.

The 1925 reorganization of the company established the institutional responsibilities which lasted until the 1980’s: Bell Laboratories designed the network, Western Electric manufactured the telephones, cable, transmission equipment, and switching equipment, the operating companies installed the phones and billed customers, and AT&T long lines operated the long distance network.

Gifford also sold Western Electric’s international business (except Canada), which he deemed a “distraction,” to the International Telephone and Telegraph Company (ITT). (ITT has since sold a majority stake in its overseas telecommunications business to form the joint venture Alcatel N.V., which remains one of the world’s top two producers–along with Lucent Technologies–of telecommunications equipment). Overseas manufacturing was a long-standing tradition at Western Electric by 1925. By establishing factories and management all over the world, Western Electric had become one of the first modem multinational corporations. In 1882, shortly after Bell had brought Western Electric into the fold, Western opened a manufacturing plant in Antwerp, Belgium. A plant in England followed shortly thereafter. Western Electric’s international operations expanded to include every country with a major telephone system.

In Japan, Western Electric first sold equipment in 1890, then in 1899 helped form the Nippon Electric Company (NEC). This was Japan’s first joint venture with an American firm; Western Electric’s original stake was 54 percent. The joint venture originally distributed telephone equipment from the United States for the Japanese Ministry of Communication, the predecessor to Japan’s telephone utility company, now called NTT Public Corporation. NEC began manufacturing soon after, and in the second decade of the century began to import electrical appliances, such as electrical fans, from Western Electric. A memo written in the 1960’s by NEC president Koji Kobayashi reflects the strong ties his company still felt to Western Electric: “Western Electric is the foremost manufacturer of communications equipment in the world, and as its offspring our company has a glorious heritage. That is why we have sometimes been called ’the Western Electric of the Far East.”’

As happens so often to companies that either were first movers or achieved early industry dominance, AT&T and Western Electric both created the entities that ultimately proved to be their greatest competitors. In the case of AT&T, this meant the regional Bell Companies in the United States; in the case of Western Electric, this meant international competition: many of Western Electric’s principal competitors–including Northern Telecom, Alcatel N.V. and NEC–had roots in Western Electric.

Graybar

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Western Electric became one of the largest distributors of electrical equipment in the United States. In some respects, this was a continuation of the original business of Gray and Barton: selling call bells, burglar alarms, etc. As demand increased, Western Electric stocked items made by dozens of electrical manufacturers, including Sunbeam lamps, sewing machines, electric fans, washing machines, vacuum cleaners–even toy ranges. The company’s catalogue grew to 1,300 pages, as the Western Electric name in electrical appliances rivaled those of General Electric and Westinghouse.

In 1925, the company announced that what was once called the supply department would be organized as a separate corporation called the Graybar Electric Company, Inc. (after Western Electric founders Elisha Gray and Enos Barton). Three years later, ownership of Graybar passed to its employees.

The Great Depression

The Western Electric News, the company organ since 1912, ended its run in 1933. The next year, The Hawthorne Microphone temporarily ceased publication. There would have been little good news to report. The Depression’s shrinkage of the American economy was deeply felt at Western Electric, where sales fell from a high of $411 million in 1929 to less than $70 million in 1933. Employment at the Hawthorne plant fell from a high of 43,000 in 1930 to about 6,000 by 1933. The company, like the federal government, resorted to a “Make Work” program at its three major plants in Baltimore, Chicago, and Kearny, New Jersey. The company paid its employees to make “articles in general demand” from furniture to cigarette lighters in order to keep them employed, then it distributed the goods–at cost–through the company stores.

At the time, telephones were not “articles in general demand.” The 1930’s were the only decade in the twentieth century when the number of telephones in the United States decreased. During the depths of the Depression, the number of telephones in use fell from 16 to 13 per 100 population; by the late 1970’s, the number had surpassed 75 per 100 population. In the 1930’s, then, telephones were still a luxury enjoyed by a minority rather than a necessity available to most. The 1936 Presidential election provided an indication of the nature of phone demand at the time. The Literary Digest conducted a telephone poll asking respondents which presidential candidate–the Democrat Roosevelt or the Republican Landon–they preferred. The poll’s respondents chose the Republican challenger; President Roosevelt–whose criticisms of “economic royalists” were not designed to curry favor with the upper middle class who had telephones–won in the greatest landslide in history. In a time of great economic distress, spending on anything but necessities usually falls, and the telephone had not yet attained the status of necessity in America–hence Western Electric’s hard times.

World War II

World War II revived America’s economy, including demand for Bell System services. During the first year of American involvement in the war, 1942, the number of telephones in the United States had increased about 50 percent from 1933 levels. From 1939, when the telephone was first employed as a “weapon of preparedness,” until 1945, the number of Bell System long distance calls quadrupled. The nature of demand had changed significantly. Most of Western Electric’s products for the Bell System during this period were radio and wire communications equipment for war use at Army and Navy bases and defense contractors across America. Western also created the communications nerve center used to direct the entire defense effort, installing the world’s largest private branch exchange (PBX) at the Pentagon in 1942, with 13,000 lines of dial PBX equipment and 125 operator positions.

The company also produced equipment for overseas use. New telephone centers sprang up in previously sparsely populated areas all over the world, to keep up with the needs of America’s far-flung military installations. The company manufactured cable and wire, switchboards, and other equipment to meet Lend-Lease commitments in foreign countries. Western Electric also produced specialized communications equipment for observation of the enemy, most notably in the area of radar.

RADAR–RAdio Detection And Ranging–is a method of detecting, or measuring distance from, objects that are either far away or hidden by clouds or darkness. It uses radio waves to detect and locate either fixed or moving objects. It is similar to radio communication in that it involves one-way communication, but it is different from radio broadcasting because it gathers information rather than giving it out. Radar was invented in the mid-1930’s in England, where it was effectively used against the Luftwaffe during 1940’s Battle of Britain. By then, Western Electric had already contracted to build radar for the American government. In October 1941, the first group of twelve field engineers were assigned to train enlisted men in how to use radar; by 1943 the group had grown to 600. The number of varieties of radio offered by the company had grown, also, to a total of 70 varieties. At the outset of the war, the radar capacities of Germany, England, and the United States were roughly equivalent, but thanks to the innovative efforts of Bell Laboratories, America was the world leader by war’s end–and Western Electric had provided roughly half of the country’s radar needs. Army ground and air forces, Navy ships, submarines, and planes, and Marine landing forces all employed Western Electric radar systems. Radar comprised about 50 percent of the company’s war production–the rest going to radio and wire communications equipment designed for war purposes.

The demand for radar systems taxed Western’s production capabilities. The Hawthorne, Kearny, and Point Breeze plants took on what work they could, set up sixteen satellite plants, including a former shoe plant and a former laundry, in nine cities, then fanned the rest out to thousands of subcontractors. A slot machine manufacturer produced antennas, a bicycle manufacturer built metal frames. Manpower was another challenge: there were not enough men to do the job, so Western hired increasing numbers of women. In 1941 women comprised 20 percent of the company’s workforce; by 1944, they were 60 percent.

World War II proved a watershed for Western Electric. On the eve of the conflict, roughly 90 percent of demand for Western Electric’s products came from one customer: the Bell System. By 1944, roughly 85 percent of demand for Western Electric’s products still came from one customer, but that customer was now the federal government, for which the company provided more than 30 percent of all electronic gear for war. While the immediate aftermath of the war brought a swift reduction in defense needs, Western Electric’s performance established a relationship that continued throughout the Cold War. When a 1956 consent decree ordered the Bell System to abandon non-telephone business, the one major exception was defense work.

Cold War Communications Systems

The twenty years following World War II appeared to offer Americans realization of their fondest hopes and their gravest fears simultaneously. Any expectations of a postwar return to Depression were soon put to rest by the greatest period of prosperity any nation has ever experienced. At the same time, Americans paid a stiff price for their good fortune: an extended arms race with the Soviet Union punctuated by periodic threat of another World War. During this uncertain time, Western Electric was actively engaged in both helping Americans realize their hopes–meeting the consumer demands of “the Affluent Society”–and in assuaging their fears of Soviet attack. For the first time, the company was fully engaged both in meeting demand for civilian goods and services, and in fulfilling major defense contracts.

Western Electric’s relationship with the government, which had greatly accelerated during World War II, had not ended in 1945; it was just beginning. In the post-World War II era, the increasing role of electronics in military defense meant that Western Electric continued to provide important service to the federal government. This involved a range of projects, from guided missiles to military communications to radar to atomic energy. By the end of the 1950’s, about 18,000 Western Electric employees were engaged in defense work alone.

There was much to work on, from the Nike guided missile program beginning in 1950 to computer-assisted air defense centers in 1958 to the emergency installation of switchboards and long-distance channels in Florida during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

The most challenging of all the projects was done during an earlier volatile and dangerous phase of the Cold War–the mid-1950’s. Western Electric acted as general contractor for the erection of one of the biggest military engineering jobs in history–a 3,000 mile system of radar outposts across the Arctic to detect approaching bombers, called the Distant Early Warning Line (DEW Line). Awarded the contract in December 1954, Western Electric used the development work of Bell Telephone Laboratories and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and enlisted the assistance of 2,700 U.S. and Canadian suppliers and contractors.

The biggest threat to the project did not come from the Soviets, but from the forbidding Arctic weather. To protect themselves against -40 degree temperatures, compounded with stiff winds, Western Electric men wore 30 pounds of clothing and carried twenty-pound sleeping bags whenever going out for a stroll. The logistical challenges were enormous, involving bulldozers, enormous quantities of steel and cement, hundreds of miles of cable, not to mention provisions for the workmen. Supplies had to be shipped during the few weeks in late summer when the Arctic Ocean was sufficiently free of ice to navigate safely.

The Arctic segment of the job was completed on schedule in July 1957. In the Spring of 1959, Western Electric completed communications and electronics phases of the 700-mile westward segment of the DEW Line through the Aleutians, and in November 1961 completed the 1,200-mile eastern segment to Iceland. The New York Times called the DEW Line “one of the modem wonders of the world.”

The 1956 Consent Decree

The value that the government perceived in Western Electric’s defense work was recognized in 1956. The culmination of an antitrust case filed by the Department of Justice in 1949, the 1956 consent decree ordered the Bell System to divest all of its non-telephone activities–except those involving national defense.

The consent decree also called for Western Electric to relinquish its 40 percent interest in Northern Electric of Canada, the last vestige of its international operations. Begun as the mechanical department of Bell Canada in 1882, Northern Electric & Manufacturing Company Limited was incorporated in 1895. In 1914, Northern Electric merged with a manufacturer of rubber-coated wire for the electrical industry. The consolidated company expanded well beyond telephone equipment. By the 1930’s, Northern Electric was selling radio and broadcasting sound equipment, electric sound equipment, and other lines of electrical equipment. Throughout this period, Northern acted as a branch plant of Western Electric.

The government’s decree not only shrank the Bell System, but it created a new competitor, now called Northern Telecom. Today, this onetime Western Electric subsidiary is a global giant, selling products in more than 80 countries manufactured in its plants in Canada, France, China, and other countries–including the United States. In 1990, Northern Telecom, the world’s sixth largest supplier of telecommunications equipment, vaulted into the third spot by purchasing the British firm STC PLC–a onetime manufacturer for Western Electric.

The Affluent Society

In 1928, AT&T’s vice president of publicity, Arthur W. Page, made a revolutionary proposal: to provide the public with a choice of various styles and colors of phones. Page noted that Western Electric made 142 different kinds of switchboard cable, but customers were only allowed to choose between “one black desk set, a hand set, a wall set, and one of those black buttoned inter-communications systems.” The lesson of Henry Ford and automobiles was fresh in Page’ s mind: “He made one little black instrument, too, and it did just what ours did: when it got started, it went fine, and so did ours. But, you know, Henry has recently come to the point where he realized he had to make a change and I think now that he has made a lady out of Lizzie, we might dress up these children of the Bell System.”

The Great Depression and World War II temporarily stemmed America’s tide of enthusiasm for choices of style and color. The post-World War II era brought the United States the greatest harvest of economic abundance any country has ever experienced. Postwar re-conversion addressed pent-up demand in all sectors of the economy, including telecommunications. Civilian orders had accumulated (called “held orders”), until about two million people were waiting for telephones. Freed of war commitments and now able to address civilian concerns during the first full year of peace, Western Electric delivered roughly two and one-half times its 1941 civilian output.

Page’s vision for the telephone consumer was not realized until the 1950s, when demand for telephones skyrocketed. By 1957, the number of telephones in the United States was three times its 1939 level, and more than 70 percent of American households had the device. Meanwhile Western Electric’s engineers had been working for years on realizing Arthur Page’s vision. In 1954, Western Electric mass-produced color telephones for the first time, and the next year began work on the Princess telephone. Industrial designer Harry Dreyfuss, who had assisted Bell since the early 1930’s, worked with Bell Labs engineers and Western Electric’s Indianapolis Model Shop to create a model that was lighter and smaller–designed for use on night tables–than the standard model. The Princess had an illuminated dial, and came in five colors. Test marketed in Colorado, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Illinois, the Princess was a smashing success.

The Princess proved to be just one of many Western Electric innovations at the time. The Indianapolis Model Shop was also working on other phones we now take for granted: phones with a dial in the handset, and touch tone phones. At the same time, the Northwestern Bell Telephone Company was experimenting with a novel way to market Western Electric’s products. The new Telephone Shop in Minneapolis, forebear of today’s Phone Stores, demonstrated telephone equipment and services in the store to customers, who could then order it “just as they would order merchandise from any other store.”

Electronic Switching & the Transistor

The boom in telephone use required other innovations which were not as visible as the Princess phone. By the 1960’s, projected phone use was so great that the existing network might soon be unable to keep up with demand. In 1963, the Western Electric’s first electronic switching system, a private branch exchange (PBX) was introduced at Cocoa Beach, Florida. Two years later, at New Jersey Bell’s Succasunna exchange, the first commercial electric central office appeared. By 1970, there were 120 such offices, servicing nearly two million customers.

The road to electronic switching had been a circuitous one, which started in the 1930’s, and had led to the development of the transistor. In 1936, Bell Labs director of research, Mervin J. Kelly, told physicist William Shockley of the vacuum tube division how important development of an electronic telephone exchange might become. Shockley, working with Bell Labs physicist Walter Brattain, sought to develop an amplifier which required less power and generated less heat than the vacuum tube. Just as their research got going, the two were diverted to war work.

After the war, a third physicist, John Bardeen, joined Shockley and Brattain on the project. In December of 1947, they succeeded in creating the transistor, thereby ushering in the modem electronic era, the era of communications satellites, the computer industry–and the electronic switching of telephone calls. In 1956, Bardeen, Shockley and Brattain were awarded the Nobel Prize for their work, which thus far has been the most famous achievement by Bell Labs.

Cellular Phones

The post-World War II era brought a number of other developments out of Bell Labs, from the solar cell to the laser, with wide-ranging implications. One advance in the 1960’s dealt more directly with telephony, allowing people to conveniently use the phone system from moving vehicles. By then, the Bell System had a long history of development in mobile radio telephony. As early as 1924, Western Electric had designed a system of mobile communications for the New York City Police Department. In 1946, the Bell System introduced the first mobile telephone system in St. Louis. Over the next few years, the service spread throughout the country. But as there was a single antenna site in a region, only a few calls could be handled at any one time. In the 1960’s, Bell Labs had made the breakthrough which established mobile telephone as we know it today: a series of radio transmitters in hexagonal “cells.” As a vehicle moves from one cell to another, electronic switching equipment transfers the call to another transmitter. The system of relatively weak transmitters and concomitant multiple use of radio frequencies yields calling quality similar to that of home or office, and the ability to get a line quickly.

After the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) set aside frequencies for mobile communications, AT&T field tested its new system in 1978 in Chicago. Three years later, the FCC authorized commercial usage of the system, a move AT&T vice president James R. Billingsley said “pulled the regulatory cork on a technological triumph that’s going to work wonders for our nation over the years.” AT&T’s “Advanced Mobile Phone Service,” began operation in Chicago in 1983. AT&T manufactured the antennae, receivers, transmitters for the local cellular companies, and the phones themselves–for awhile. Japanese competition drove AT&T out of the telephone market in 1986, and left the company as a leading supplier of the phone company equipment, which it remains today.

In the early 1990’s, however, an astonishing thing happened with respect to cellular phones. AT&T conducted a survey, asking respondents whose cellular phone they preferred to use. AT&T placed second, although the company no longer made such phones! The company got back into the market, and is now one of the leading cellular phone manufacturers, a rapidly growing market of more than 25 million in the United States alone.

The 1984 Breakup

Just as the FCC was sanctioning AT&T’s addition of commercial cellular phone service, the Department of Justice was engaged in a larger exercise in subtraction: the breakup of the Bell System. Through the years, AT&T had been the target of antitrust investigation. In 1913, after discussions with the attorney general’s office, AT&T vice president Nathan Kingsbury agreed to allow other telephone companies to engage in toll service over Bell System lines, and to dispose of the controlling interest in Western Union stock AT&T had acquired in 1909; in return, the government sanctioned the Bell System’s limited monopoly and national telephone system.

The “Kingsbury Commitment” did not put an end to government investigation of the Bell System. The Federal Communications Act of 1934 had established the Federal Communications Commission, with jurisdiction over telephones previously held by the interstate Commerce Commission. One of the FCC’s first acts was to investigate AT&T, paying particular attention to the relationship between Western Electric and the operating companies: did Western overcharge for its equipment, and recover the excess over “market” price in exorbitant rates to consumers? The FCC ’s principal investigating attorney, Holmes Baldridge, became chief antitrust litigator of the Justice Department after World War II, and pursued the Western Electric/operating companies relationship again. The Eisenhower administration’s Justice Department was less antitrust-minded than its predecessors, so the 1956 Consent Decree allowed the Bell System to keep Western Electric in the fold, but stripped the Bell System of most of its non-telephone business, and its interest in Northern Electric.

In 1974, the Justice Department began antitrust proceedings to seek dismemberment of AT&T, which was the largest corporation in the world. Eight years later, as a Modification to the 1956 Final Judgment (MFJ), AT&T agreed to divest its 22 wholly-owned operating companies which provided local exchange service. AT&T’s work force shrunk from more than a million to less than four hundred thousand. In exchange for the divestiture, AT&T was allowed to compete in non-telephone businesses–which the 1956 consent decree had forbidden–such as computers and information services.

AT&T also abandoned two names which had been associated with the company for more than a century: Bell and Western Electric. The government ordered that AT&T forfeit use of the Bell name and logo to the operating companies (excepting the name Bell Laboratories). Western Electric disappeared as a separate entity when AT&T restructured according to its new competitive situation. One of the two primary parts of the new, smaller, AT&T was the old company’s long lines department, now called AT&T Communications, which offered regulated long distance service. The second part of the new company, called AT&T Technologies, inherited the other two segments of the old Bell System: equipment manufacture and supply (the old Western Electric) and research and development (Bell Laboratories).

AT&T Technologies, the name of which symbolized the company’s long-standing heritage of research and innovation, included five segments. Network Systems, the largest segment, represented the heart of the old Western Electric: production of telecommunications equipment. Information Systems explored the possibilities of integrating voice and data capabilities into information networks. Consumer Products serviced the new market for the sale of residential telephones and telephone equipment through Phone Stores and other retail channels. Technology Systems concentrated on computer applications of Bell Laboratories research, from components to systems, and government work. Finally, International pursued overseas markets for switching and transmission systems.

Subsequent to 1984, the company restructured AT&T Technologies, and abandoned its name. Until September of 1995, the Network Systems Group included the largest segment of the old Western Electric charter, including the company’s growing presence in international markets for telecommunications equipment.

Going Global (Again)

Just prior to disappearing as a separate entity, Western Electric had returned to overseas markets after a long absence. The company’s 1977 agreement to supply the government of Saudi Arabia a microwave system of about 300 radio relay systems and its 1979 contract to provide the government of Taiwan with an electronic switching system, marked Western Electric’s first overseas ventures since 1925. The two agreements did not, however, a global giant make: at the time of the 1983 divestiture, AT&T had fewer than 100 employees outside the U.S.

After the MFJ, AT&T intensified its overseas efforts, forming a joint venture in the Netherlands with N.V. Philips to produce telephone network equipment. This joint venture eventually became AT&T Network Systems International, in which N.V. Philips no longer plays a role. Joint ventures in Italy, Spain, Ireland, Denmark, Korea, and Japan followed in the 1980s. The company also established manufacturing plants in Singapore and Thailand to manufacture consumer telephone equipment, and in the Netherlands, Taiwan, and Korea to produce switching equipment.

In February 1991, AT&T displayed a spectacular example of its growing international capabilities. A convoy of AT&T employees and equipment followed US troops into just-liberated Kuwait to restore telephone service: Operation Desert Storm was followed by what later was dubbed “Operation Desert Switch.” Using a seven-meter satellite dish, AT&T switch and phones, the company restored outgoing international service less than 48 hours after Kuwait’s February 28 liberation. A few months later, AT&T delivered two switches and an earth station to restore full service.

In 1993, AT&T signed a historic agreement with the People’s Republic of China, involving research, development and manufacturing of switching and transmission systems, wireless systems, and customer equipment. China, with only two phones per 100 people (compared to more than 80 phones per 100 people in the United States), represents the largest of a number of overseas markets which AT&T was poised to explore; by 1993, AT&T had more than 53,000 employees abroad.

AT&T’s establishment of a global business offered the company new opportunities, but in many respects, a global presence was nothing new for the old Bell System. On the eve of World War 1, Western Electric’s overseas locations included Antwerp, London, Berlin, Milan, Pairs, Vienna. Budapest, Tokyo, Buenos Aires, Sydney–and St. Petersburg.

Today Lucent Technologies sells phones in Russia and Ukraine, marking the latest chapter in the company’s roller-coaster relationship with Russia and the Soviet Union. Before the 1917 Russian Revolution, Western Electric had a manufacturing facility in St. Petersburg. The superintendent of the plant was murdered in his living room by revolutionaries, and the operation was nationalized. Western Electric’s next contact with the Soviet Union came when the company produced telephone systems for America’s ally during World War II. The subsequent onset of the Cold War changed Western Electric’s relationship with the Soviets again.

In 1990–before the crumbling of the Soviet Union–the company reached an agreement to provide switching and transmission equipment to Armenia, which became the first Soviet Republic to establish independent international phone service. Previously, all of the Soviet union’s international calls routed through Moscow–where central authorities determined which calls had priority, and where limited capacity created overload problems. In January of 1992, only 44 days after Ukraine declared its independence, AT&T, PTT Telecom of the Netherlands, and the Ukrainian State Committee of Communications formed a joint venture to build, operate, and own a long-distance network for the new republic. At the system’s February 1993 inaugural, Ukraine Minister of Communications, Oleh Prozhyvalsky, said: “This marks a milestone in the modernization of our telecommunications infrastructure.” It was, however, much more than that. By offering communications services to Armenia, the Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, Poland, and Czechoslovakia, AT&T helped usher in the new post-Cold War world.

Consumer Products

For AT&T, the New World Order was both an international one, and a very competitive one–especially in consumer products. In the first couple of years after divestiture, AT&T reached a low point in the residential telephone equipment market. FCC regulations once allowed telephone companies to dictate to customers whose equipment they could use. This meant that the vertically integrated Bell system could assure that their manufacturing branch, Western Electric, would have the same market share providing equipment that the phone companies did in providing service. Telephones were leased only, and a part of an end-to-end service package. That changed in the 1970’s, when the FCC ruled that customers could connect their own equipment to the telephone network. It further required that each manufacturer of telephones equip them with standard plugs which fit into jacks provided by phone companies. These changes opened the door for independent manufacturers of telephone equipment, and by 1978, one million phones were sold in department stores and electronics shops. AT&T responded by accelerating their production of phones in various styles and opening phone stores which allowed customers to choose a phone, take it home and plug it in, rather than wait for a repairman to do so.

In the years immediately following divestiture, telephone customers chose increasingly to buy, rather than lease phones. AT&T rental revenues declined form $7.2 billion in 1984 to $3.0 billion in 1988. That would have done AT&T little harm if the company made up the difference by selling phones. It didn’t. AT&T phones had been designed for a lease environment: they lasted forever, and were pretty homogenous. Customers in 1984 and 1985 flocked to cheaper phones with more features. AT&T considered abandoning the market entirely, as they briefly did with cellular phones, but decided instead to fight back.

Bell Laboratories designed less costly phones, which AT&T marketed more aggressively. By 1987, AT&T sold phones through 7,000 retail outlets plus 450 Phone Centers. The company also successfully entered the markets for cordless phones and for telephone answering machines. In 1987, the Washington Post reported: “Not all companies decide to raise the white flag in the face of a competitive battle … and (some) come out of the fight a winner. American Telephone & Telegraph is a case in point.” AT&T recaptured leadership of the market for residential telephones. One reason is that while in the mid-1980’s, the company reduced costs in the consumer products area dramatically–50 percent in three years–superior quality remained.

Capitalizing on growing consumer impatience with the low-quality, “throw away” telephones, AT&T ran a series of successful commercials calling attention to the problems of the competition’s “second-class phones.” By contrast, one consumer reported that after his AT&T cordless phone fell on the driveway and was crushed by a half-ton truck, “I picked it up, switched it to talk, and couldn’t believe it still worked.” After gluing the pieces together, he continued to use the phone. Little wonder that a 1988 Gallup survey rated AT&T one of America’s top ten companies in quality, and the company continued to win plaudits in the 1990’s.

Western Electric and the Quality Movement

In October 1994 AT&T Power Systems became the first U.S. manufacturer to win Japan’s Deming Prize, which salutes companies for successful dedication to the concepts of Total Quality Management. Two years earlier, AT&T Transmission Systems had won a Malcolm Baldridge Quality Award. While some saw these awards as evidence that American business had finally caught on to Japanese management principles, Western Electric had long been a seedbed for the modem quality movement. Andrew M. Guarriello, chief operating officer of AT&T Power Systems noted that “the roots of today’s Total Quality Management can be traced to the work of three AT&T scientists and quality pioneers–Walter Shewhart, W. Edwards Deming, and Joseph Juran. This award tells me quality in manufacturing has come full circle.”

Over the years, quality assurance methods at Western Electric and elsewhere have evolved along with changes in the relationship between workers and their output. At the time of the company’s founding, individual artisans checked their own work. In 1876, the seven year-old Western Electric was recognized for the quality of its products at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, winning five first-class medals for its apparatus. While the company proved that it could create products of the highest quality, doing so consistently for large-scale output was something else entirely. At the time of the company’s 50th anniversary, H. F. Albright, Western Electric’s vice president in charge of manufacturing, recalled the challenges of the 1880’s: “We were supposed to produce forty-eight telephones and transmitters a day. Some lucky days we got perhaps as high as a dozen or two accepted. Other days our whole shipment was rejected. The shop superintendent quit in despair, but the shops kept everlastingly at it and at last succeeded in shipping telephones that would stay shipped.”

By the turn of the century, Western Electric had trained individuals as inspectors to assure specification and quality standards, in order to avoid sending bad products to the customer. In the 1920’s, Western Electric’s Dr. Walter Shewhart took manufacturing quality to the next level–employing statistical techniques to control processes to minimize defective output. When Dr. Shewhart joined the Inspection Engineering Department at Hawthorne in 1918, industrial quality was limited to inspecting finished products and removing defective items. That all changed in May 1924. Dr. Shewhart’s boss, George Edwards, recalled: “Dr. Shewhart prepared a little memorandum only about a page in length. About a third of that page was given over to a simple diagram which we would all recognize today as a schematic control chart. That diagram, and the short text which preceded and followed it, set forth all of the essential principles and considerations which are involved in what we know today as process quality control.” Mr. Edwards had observed the birth of the modem scientific study of process control. That same year, Dr. Shewhart created the first statistical control charts of manufacturing processes, which involved statistical sampling procedures. Shewhart published his findings in a 1931 book, Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Product.

Dr. Shewhart’s work had limited impact beyond Western Electric manufacturing until the late 1930’s. W. Edwards Deming of the War Department–and briefly an employee of Western Electric–invited Shewhart to give a series of talks, which Deming later edited for publication. In 1947, the newly-formed American Society for Quality Control began recognizing individuals with the Shewhart Medal for contributions to the field. The first recipient of this annual award: Dr. Walter Shewhart. By then, Joseph Juran of Western Electric and Harold Dodge of Bell Labs had made major quality control contributions to the federal government’s quality efforts. During World War II, they and other engineers and statisticians from Western Electric and Bell Labs worked for the War Department, creating a series of sampling inspection plans that were published as the MILSTD (military standard) series. MILSTD set the standards that are still used in America and throughout the world.

After the war, America exported quality expertise to Japan. The Civil Communications Section (CCS) of the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers was rebuilding Japan’s telecommunications system–and improving its quality. CCS arranged for Western Electric and Bell Labs engineers to teach fundamentals of quality to a generation of Japanese equipment manufacturing executives–who then showed the world how valuable those lessons were.

The most notable agents of this effort were Juran, who spent the first dozen years of his career at Western Electric, and Deming, who had spent two summers working there. Juran, influenced by his experiences at Western Electric, emphasized the value of training programs in quality. Only through the use of such programs could every worker in the company learn the necessary quality control techniques–a necessary condition to the goal of continuous quality improvement.

At Western Electric, this expertise on quality was communicated to the shop floor–most dramatically by Bonnie Small who joined the Hawthorne quality assurance department in 1940. Her experiences there during World War II convinced her that Shewhart’s abstract ideas alone were of little help to newly hired workers, so she set out to translate the ideas of Shewhart into practical methods. After joining the Allentown Plant in 1948, Small assembled a committee of quality professionals throughout Western Electric to write a handbook for the factory. This handbook represents the confluence of Western Electric’s long-standing traditions of quality control and of education and training. Much of the material for the book was based on Western Electric training courses given to managers, engineers, and shop floor people from 1949 to 1956. The “Western Electric Statistical Quality Control Handbook” appeared in 1958, and has been the shop floor bible of quality control throughout the world ever since. It remains in print, available from the company today.

Quality and technical innovation have become two of the hallmarks of success in today’s global competition in manufacturing. Quality and technical innovation are also the basis of Western Electric’s heritage in manufacturing, which Lucent Technologies will inherit.

Motion Picture Sound (Sidebar #1)

In 1922, Research Administrator E. B. Craft decided to direct the company’s developments in amplifiers, loudspeakers, microphones, and electronic recording in a new direction: towards sound motion pictures. Efforts towards that end had been tried since the dawn of motion pictures in the 1890’s, most notably the introduction of the Kinetophone from Thomas Edison’s laboratory in 1913. The Kinetophone’s poor synchronization and sound quality proved more a distraction than an enhancement to films. Edison’s failure made Hollywood moguls wary of expending much time or effort on sound–offering an opportunity to other innovators outside of the motion picture industry.

By 1923, a number of companies were working on sound developments, but Craft was undaunted by the competition. He wrote Frank Jewett, vice president in charge of research, “it seems obvious that we are in the best position of anyone to develop and manufacture the best apparatus and systems for use in this field.” Craft turned out to be right. Western Electric developed an integrated system for recording, reproducing and filling a theater with synchronized sound. By 1924, Western Electric was ready to sell its system to Hollywood.

Western attracted the attention of a second-tier motion picture studio called Warner Bros., and the two companies formed a joint venture, the Vitaphone Corporation, to experiment in the production and exhibition of sound motion pictures. Four months later, the new system, called Vitaphone, debuted with the opening of “Don Juan,” starring John Barrymore, at the Wamer’s Theatre in New York City. Preceding the film were a series of short sound films, rather than the usual live vaudeville acts. As for the main feature, an electrical sound system–carrying the recorded strains of the New York Philharmonic–replaced accompaniment by live musicians. The system was a hit, even if the film wasn’t: Quinn Martin wrote in the New York World, “You may have the ‘Don Juan.’ Leave me the Vitaphone.”

Western Electric formed a subsidiary the following January to handle Western’s non-telephone interests. Electrical Research Products, Inc. (ERPI) developed and distributed studio recording equipment and sound systems to the major Hollywood studios. Recognition for Western Electric’s contributions to the film industry soon followed. In 1931, ERPI won an award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for technical achievement. ERPl’s system of noiseless recording was cited as “outstanding scientific achievement of the past year.” ERPI also made sound equipment for movie theaters, which it leased, rather than sold- just as the Bell System had leased out the telephone equipment Western produced. ERPI equipped 879 movie theaters in 1928, and 2,391 in 1929. By 1932, only 2 percent of open theaters in America were not wired for sound. Western Electric proved better at wiring the nations’ theaters than at maintaining that customer base, however, and ERPI abandoned the motion picture theater business in 1937. The company continued to produce sound equipment for movie studios until 1956, when as part of the consent decree it abandoned most non-telephone enterprise. The company left a legacy in the motion picture industry, one reminder of which is the credit at the end of many films from Hollywood’s Golden Age: “Sound by Western Electric.”

The Hawthorne Experiments (Sidebar #2)

From 1924 until 1933, the Hawthorne plant was the site of a series of experiments conducted under the auspices of the National Research Council. The initial studies involved the impact of changes in lighting levels on the productivity of several groups of workers. The first two sets of tests showed that increased levels of supervision played a much larger role in productivity increases than levels of illumination.

The most involved of the experiments, the relay assembly test room experiment, involved isolating six women, then measuring their production, health, and social interactions in response to changes in working conditions, such as the number and duration of rest periods, length of the work day, and the amount of food they ate. Productivity increased as each improvement was introduced, until the crucial twelfth test, in which researchers removed the special conditions. Productivity increased again! One of the researchers called the twelfth test “the great

éclaircissement, the new illumination, that came from the research.” The experiments raised the possibility that, as Thomas J. Peters and Robert Waterman put it, “it is the attention to employees, not work conditions per se, that has a dominant impact on productivity.”

The impact of the experiments has been felt worldwide, and by many generations. In the 1950’s, a number of Japanese executives visited Western Electric and told their hosts that, Management and the Worker, a book summarizing the findings from the Hawthorne experiments, was required reading in Japanese schools of management. The phrase “Hawthorne effect” has come to mean any unexpected outcomes from non-experimental variables in social or behavioral sciences. The Hawthorne experiments have been elevated to what one historian calls the “status of Creation myth” in many fields that study the workplace, from sociology to psychology to anthropology.

Return to top of page (table of contents)

Mama Visits the Factory

The following article was contributed to this web site by Loren Haroldson:

Western Electric’s factory tours for its own workers and their families – and a good time had by all.

Condensed from “Current History, January 1939” - © 1938, 63 Park Row, N.Y.C.

Morris Markey

One day a committee representing the 15,000 workers at Western Electric’s biggest plant – Hawthorne, near Chicago – appeared in the front office. Their grievance was a rather odd one. “All of us work on parts of things,” they said. “We never see the complete product put together. Couldn’t we figure out some way for all our people to go through the whole factory, and see what the others are doing, and understand the whole process that goes into the stuff we make?”

The way was figured out. I didn’t see it work at Hawthorne, but I did go to the Baltimore plant and to the Kearny, N. J., plant when Open Houses were held at those places.

For the fortnight of Open House, the hours of the working day for key workers in the departments were changed: 2:15 in the afternoon to 11 oclock at night. Then, every afternoon and evening, after the regular working day was over, the rest of the employees had opportunity to pass through the factory - into corners they did not know existed, past operations they had never seen before.

But the interesting thing, to me, was the fact that the touring workmen brought their families with them - their wives and children, their in-laws and sweethearts and fellow lodge members, to see what sort of place Joe worked in, what he did to make a living and how he went about doing it.

They flocked through the immense factories in fascinated crowds, about 5000 of them every night. It took three hours of tough walking to see what was to be seen. But they had a wonderful time, and for a simple reason: That remote and rather forbidding abstraction, “The Factory’’ where Dad or Cousin Joe worked, was being rendered then and there into a human sort of place which all the family could understand and talk about over the supper table.

Organized tours for the general public through the big automobile factories, steel mills, power plants and coal mines are now commonplace. But this Open House of the Western Electric Company is different. Since Western Electric makes telephone equipment and for all practical purposes has only one customer – the Bell System – it need not impress the general public. But in these good-will tours for its own workers it has found something new in industrial relations – something affecting the family and social circle of every employee.

I followed one family for a while: Dad all dressed in a blue serge suit and a derby hat, Mom in her best party dress, two high school boys and a girl of ten. For a while they walked past machines that Dad himself had never seen before, workmen who were strangers to him. He was deeply interested, and asked questions of the men at the machines, explaining carefully who he was. Then, as we gradually drew near his own part of the factory, you could see the pride begin to rise in him.

“When do we get there, Dad?” the boys would ask. Dad lifted his hand deprecatingly. “Take it easy, he said. “It won’t run away.” He laughed. “Not that baby.”

We went down a broad aisle, and presently Dad stood back, his hands in his pockets and his hat on the back of his head, looking up at a very brute of a machine, an immense punch press that shrugged its shoulders and set down a ten-ton foot upon a plate of steel, pressing it into some weird shape.

“Well,” Dad said, “there she is.” They stared in blank-faced admiration. The boys said,” Gee-e-e!Mom, trying to conceal her interest, said, “From what you’ve been saying, I’d have thought it was twice that big.” But she didn’t mean it, and he knew it.

There were four of the machines in a row, and Dad’s was being, operated now by a tall, lean-faced man. Dad introduced him to the family, and introduced the men at the other machines, too. For the last of them, he had a particularly warm grin.

“And now, Mom,” he said, “youcan shake hands with Bill Nagle himself.”

“Well,” she said, “after all those cribbage games I’ve heard about, it seems like I know you already.”

“That’s right,” said Mr. Nagle. “I have to beat the old boy here every day at lunch hour.”

“You beat him?” Mom pretended to be outraged, and they all laughed. It seemed that Dad had been working alongside Bill Nagle for three years. But their homes were miles apart, and they never got together at night. It seemed, furthermore, that there was a Mrs. Nagle and divers Nagle children, and arrangements were made forthwith for the women folks to get together and cook a beefsteak dinner for all hands.

Dad settled down to explain his machine, in meticulous detail, to the boys. And Mom watched, with no want of pride in her round, quiet face.

All over the plant, encounters of a like sort were going forward. Above the hum and beat of the machines, voices wandered on as men explained their work and women and children listened eagerly.

At Baltimore and at Kearny numerous girls are employed, their nimble fingers working incessantly upon the more delicate contraptions that are part of transmitters and condensers and such. When the plans for the Open House were going forward, these young ladies had presented something of a problem. They had announced that they would not be content with ordinary work dresses for the occasion, but intended to do themselves out in proper style. This seemed an admirable idea until they showed up for work the first day – in silk evening dresses and the more complex variations of the modern hair-do. The crowds, quite understandably, banked deep about them.

But the boss decided that this was hardly in the mood of industrial production, and with what diplomacy he could command suggested that they wear something a trifle less ravishing in the future. The girls compromised on party frocks and dirndl prints, but even thus tamed down it was a matter for note that during all the Open House period production if anything improved. The girls worked better when they had an appreciative audience.

These matters may seem frivolous. Perhaps there is nothing of real or lasting importance in the spectacle of homey little family groups gathered about a machine, or of girls allowing vanity to impinge upon the simple business of earning a weekly wage. But I assure you that such things made a very striking contrast to the picture one ordinarily gets of that troubled mystery, the Labor Situation. People, it seemed, were not emphasizing their differences with their employers, but their common interests. Nobody seemed to be going hysterical at the ceaseless rhythm of the machines.

On the contrary, I think everybody (including myself) was a little astonished to discover that the factory was a pretty decent sort of place to work in and that the bench and the stools were peopled by quite ordinary human individuals - not nameless atoms in that amorphous molecule, Labor.

But I am no expert in these affairs. I can only report that it seemed a sensible thing, and certainly a pleasant one, to invite families and friends in to see what really lies behind the pay envelope that Dad brings home every Friday.

Return to top of page (table of contents)

Manufacturing the Future: A History of Western Electric

Adams, Stephen B. and Orville R. Butler

Published by EH.NET (February 2000)

Stephen B. Adams and Orville R. Butler, Manufacturing the Future: A History of Western Electric.

New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999. xi + 270 pp. $34.95

(cloth), ISBN: 0-521-65118-2.

Purchase at Amazon

Reviewed for EH.NET by Eric John Abrahamson, The Prologue Group.

For more than a century, Western Electric supplied equipment to AT&T’s long distance and local telephone companies as the manufacturing arm of the old Bell System. Regulators around the country hated the situation. Many believed that AT&T hid excess profits or bureaucratic inefficiencies in Western’s charges to Bell System customers. Repeatedly, the federal government tried to force AT&T to divest the company. AT&T fought these efforts and made enormous concessions to the government to retain its vertical integration - until 1995. That year, AT&T announced that it would divest what remained of Western Electric and portions of Bell Laboratories to create a new company - Lucent Technologies.