Western Electric Products- Picturephone

Ahead of it’s time - Another Bell Labs innovation!

Sewing Machine - Automatic Answering Service “Mirrophone” wire ribbon recorder/player Telephones - PicturePhone - Bell Chime

The first Picturephone test system, built in 1956, was crude - it transmitted an image only once every two seconds. But by 1964 a complete experimental system, the “Mod 1,” had been developed. To test it, the public was invited to place calls between special exhibits at Disneyland and the New York World’s Fair. In both locations, visitors were carefully interviewed afterward by a market research agency.

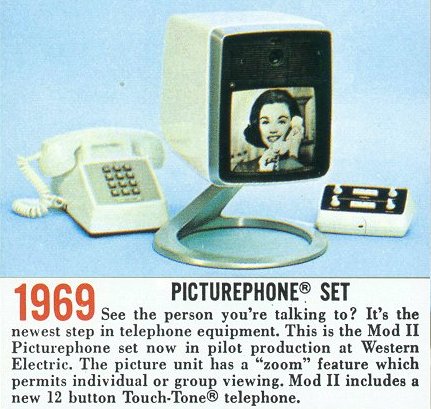

People, it turned out, didn’t like Picturephone. The equipment was too bulky, the controls too unfriendly, and the picture too small. But the Bell System was convinced that Picturephone was viable. Trials went on for six more years. In 1970, commercial Picturephone service debuted in downtown Pittsburgh and AT&T executives confidently predicted that a million Picturephone sets would be in use by 1980.

What happened? Despite its improvements, Picturephone was still big, expensive, and uncomfortably intrusive. It was only two decades later, with improvements in speed, resolution, miniaturization, and the incorporation of Picturephone into another piece of desktop equipment, the computer, that the promise of a personal video communication system was realized.

Also, there are pamphlets on the Picturephone that you can download that are at the bottom of this page.

We Offer Personalized One-On-One Service!

Call Us Today at (651) 787-DIAL (3425)

1950s

The Bell System (AT&T/Western Electric) PicturePhone (developed in Bell Labs as a prototype in 1956 (see photo above), but never test marketed until the early 1960’s) never became popular after it was briefly offered commercially in Chicago. If it had, it is doubtful that it could have been implemented on a wide scale given the technology of the time. This was, after all, before the days of microprocessors and data compression. Digital telecommunications was in its infancy.

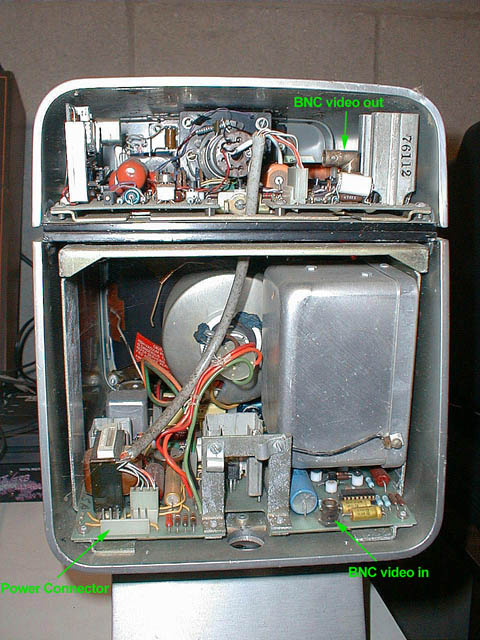

The PicturePhone was connected to the Central Office via 3 standard wire pairs (for comparison, a regular telephone line uses a single wire pair). One pair carried the 1 MHz PicturePhone video signal in one direction, the other carried video the in the opposite direction. These had to be specially equalized to carry the signal but were still otherwise just ordinary telephone wire. The third pair carried the normal 2-way voice call plus carried the TouchTone dialing to set up the call.

A PicturePhone Central Office had a second switch (an electromechanical “crossbar” switch in those days!) operating in parallel to the regular switch for those making PicturePhone calls. That takes care of local calls.

The fun comes when a call has to be connected to someone served via another Central Office. Telephone calls are multiplexed together to go from one office to another. Many calls share the same communications system whether microwave, coaxial cable, or (nowadays) fiber optic is the medium. Even when offices are connected via ordinary wire pairs many calls share the same wires. A voice channel is allotted only 3000 Hz (this is after all telephony, not 20,000 Hz high-fidelity audio!) for each direction. But a PicturePhone video signal takes 1,000,000 Hz. That’s 333 times the bandwidth! A few video calls would fill up all available bandwidth. How could they possibly have handled it? Necessity is the mother of invention so in all likelihood they would have invented video data compression in a big hurry! After all, Bell Labs was working on digital audio as far back as WWII. (You should see the electron beam CODEC tube of 1947!)

The Bell System estimated three million PicturePhone units would be operating in homes and offices by the mid-1980s, bringing in a combined revenue of $5 billion a year. Initial reaction to PicturePhone had been very positive. However, these positive marketing reactions were soon dampened by the realities of cost and the hesitation of people to be accidentally seen by others in the private affairs of their homes. AT&T abandoned its plans to market the Mod II in 1973.

1960s

From the 1993 Telephone Story Poster.

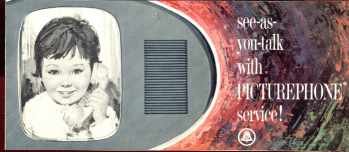

“A logical extension of today’s telephone service… BELL SYSTEM INTRODUCES PICTUREHONE SERVICE… both ends of telephone conversation are pictures; people phone by appointment from family-type booths in attended centers. Bell System PICTUREPHONE service now lets callers see as well as talk on the telephone. And ‘hands free if they wish’. For the first time people can make a visual telephone call to another city-the latest example of the research, invention and development that are constantly providing the communications we provide. The new service is being offered in the cities listed are the left. Bell Systems attendants at each local center help callers enjoy prearranged face to face visits with friends and relatives in either of the other cities.” (the cities are New York, Chicago, Washington)

1964 World’s Fair in New York - Visitors used “PicturePhone” instruments, developed by the Bell Telephone Laboratories, that transmitted voice and image between two nearby booths. Click on picture for link to Bell System’s Pavilion info. People lined up to make PicturePhone calls to a corresponding exhibit at Disneyland. First Lady Ladybird Johnson even stopped by to try it out.

The next two images on this page and their original captions have been donated by Science Service and are presented to you as they appeared in period publications. The captions were written by Science Service journalists and have been transcribed exactly. Although these images are protected by copyright, we encourage you to use them for academic and non-commercial pursuits. - The National Museum of American History.

PICTUREPHONE CIRCUIT PACKAGES

CD 1967085 E&MP130.011

Joseph A. Mazzeo of Bell Telephone Laboratories removes one of the circuit packages in the experimental PICTUREPHONE system.

The comparatively small size of the visual telephone, the PICTUREPHONE is made possible by the development of modern circuits using transistors and other miniature components.

Original Caption by Science Service

©Bell Telephone Laboratories

VISUAL TELEPHONE SYSTEM

CD 1967053 E&MP130.016

L.H. Meacham at his desk at Bell Telephone Laboratories in Holmdel, N.J. talks with and views A.D. Hall on the experimental PICTUREPHONE.

Both engineers helped develop the visual telephone system.

Mr. Meacham is using the hands-free Speakerphone while Mr. Hall at the Murray Hill, N.J. Laboratories uses the familiar handset for the call.

Original Caption by Science Service

© Bell Telephone Laboratories

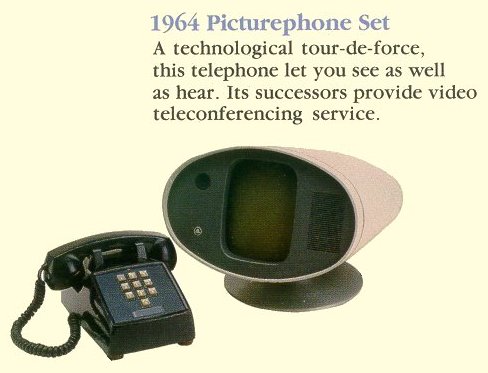

MOD I (Model one) version - From the 1965 “The Telephone Story” poster

MOD II (Model two) version - From the 1969 “The Telephone Story” poster

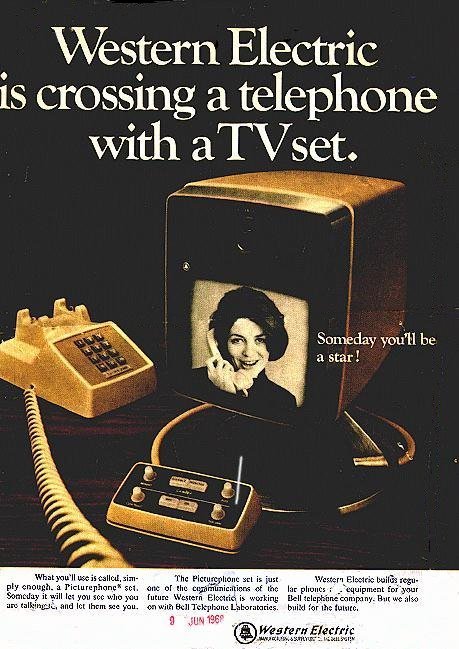

“Someday you’ll be a star!” was one of the advertising slogans the Bell System used decades ago to try to promote this high tech and futuristic communications device called the “PicturePhone”. But no matter how much the Bell System tried, it was one of the most visible flops in communications technology history.

Thomas Farley, webmaster of the Private Line web site, has recently found a picture of what he thinks is a NTT picture phone circa 1968, complete with rotary dial:

http://www.privateline.com/TelephoneHistory4/History4.htm

1970s

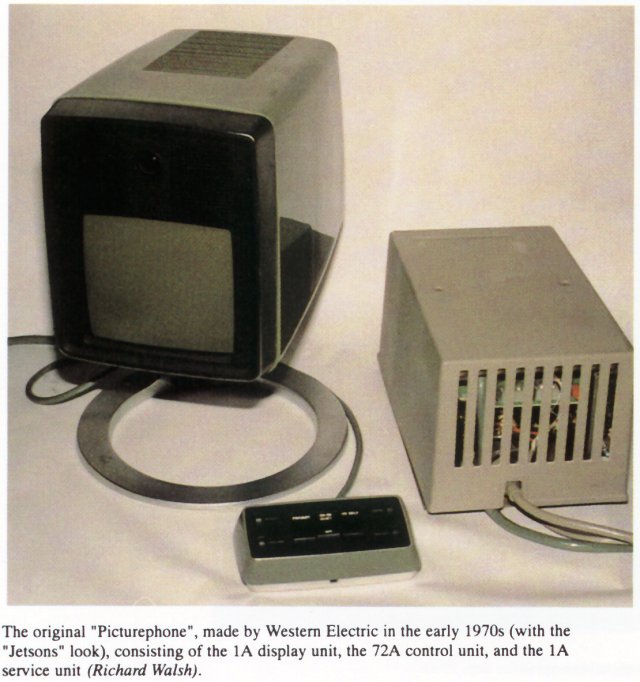

(From “100 Years of Bell Telephones by Richard Mountjoy)

Pittsburgh Mayor Pete Flaherty made the world’s first picture phone call.

Here are some photos sent from Bill Romanowski of his Picturephones (possible Bell Lab prototypes)

1990s

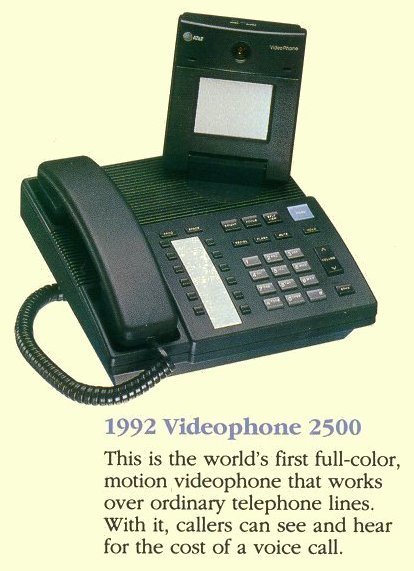

Click HERE to read article in the February 1993 issue of AT&T’s FOCUS magazine on this VideoPhone model 2500.

In 1992 AT&T introduced the VideoPhone 2500, the world’s first colour videophone that could transmit over analog telephone lines. Its prices started at US$1,500 and later dropped to $1,000. Unlike the earlier Picturephones, the VideoPhone 2500 employed digital compression methods to enable a significant reduction of the bandwidth required for full-motion video transmission. A V.34 modem was employed to transmit the compressed video signal over an analog telephone line for access to the PSTN, where the signal could be readily circuited through central-office switches. Depending on the quality of the telephone line, the VideoPhone 2500 transmitted at either 19.2 or 16.8 kilobits per second. The video compression algorithm employed in the VideoPhone 2500 was licensed to a number of Japanese manufacturers for employment in similar videophones. Nevertheless, lack of sales led AT&T to discontinue the VideoPhone 2500 in 1995.

Video phones finding niche after 40 years in development by Al Moyers

Air Force Communications Agency Office of History (http://infosphere.safb.af.mil/~rmip/97dec/intercom.htm) Note: The original web link above is no longer valid. I managed to find a text file of this article on another server at:

http://zia.hss.cmu.edu/miller/eep/news/video2.ne.txt

The Air Force is testing video telephones at locations both in the United States and overseas to provide “video morale calls” for deployed members.

“I have never seen a better morale booster,” was the report of one Air Force first sergeant during a recent test of video telephone technology at Incirlik AB, Turkey.

The video phone concept is actually more than four decades old, but new low-cost technologies are providing the Air Force a rare opportunity to permit families and deployed airmen to be able to see, as well as talk, to one another.

The idea behind the video telephone system presently being examined by the Air Force was succinctly stated in the 1960’s print advertisement of Western Electric-“crossing a telephone with a TV set.” The Western Electric advertisement showed the less-than-successful PicturePhone system which it produced in cooperation with AT&T’s Bell Laboratories.

Years before, engineers at Bell Laboratories began discussing the concept of simultaneous transmission of video and voice over telephone lines in the 1920’s.

In 1927, the Bell Telephone System sent live television images of Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce, over telephone lines from Washington, D.C. to an auditorium in Manhattan, N.Y. This was the first public demonstration in the United States of long-distance video transmission.

The first “PicturePhone” was completed by Bell Laboratory engineers in 1956. This first system was crude and cumbersome and required three standard wire pairs to operate: one pair to carry the video transmission, one pair to carry video reception, and the third to carry the audio signal. Requiring 1,000,000 Hertz of bandwidth, the PicturePhone video signal exceeded by more than 300 times the bandwidth allotted to a typical telephone voice signal.

By 1964, a somewhat improved version of the PicturePhone, dubbed the “Mod 1,” had been developed and was debuted at the New York World’s Fair. To test public reaction to the PicturePhone, visitors were invited to place calls between special exhibits of the PicturePhone at the World’s Fair and Disneyland.

Survey results indicated that most people did not like PicturePhone. The controls were awkward and the picture was small. Moreover, most people were not comfortable with the idea of being seen during a phone conversation.

However, the system’s developers at Bell Laboratories were convinced that PicturePhone was viable and could find a market. AT&T inaugurated commercial PicturePhone service between New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., June 24, 1964, with a call from Lady Bird Johnson, wife of President Linden Johnson, in Washington; to Dr. Elizabeth A. Wood of Bell Laboratories in New York City.

A three-minute PicturePhone call from Washington to New York City cost $16. The most expensive connection, between New York City and Chicago, cost $27 for three minutes. This inaugural PicturePhone service never caught the attention of consumers.

AT&T continued to believe in the viability of PicturePhone. With the beginning of commercial PicturePhone service in Pittsburgh in 1970, AT&T executives predicted that Picturephones would be in use in more than a million settings by 1980. Their estimates were far off the mark. Consumers were still not ready for PicturePhone, finding it too big, too expensive, and, for many, too intrusive.

In January 1992, AT&T executives again predicted the success of a videophone system with the introduction of the AT&T VideoPhone 2500-the first full-color, home video phone system to use standard home telephone lines.

During the system’s debut, Robert Kavner, AT&T group executive for AT&T Communications Products, said, “This is the way people want to communicate. The time is right. The price is right. The technology is right.”

AT&T executives reported that the video phone would become as popular as cordless and cellular phones. Yet, a large market has yet to be found.

According to the calculations of telecommunications author Stephen J. Maudsley, the great decrease in the cost of video telephones is due to the continued development of silicon technology. Maudsley reports the cost of a video telephone in the 1960’s was nearly $500,000. The AT&T VideoPhone 2500 was introduced in 1992 at a cost of approximately $1500 and within a year was selling for less than $1000. The video telephone system being tested by the Air Force sells for about $500 for each unit. This dramatic increase in savings, according to Maudsley, comes from two areas-the integration of functions and the compression of images-associated with the continued decrease in the size of electronic devices.

The functions required for video phone operation have been integrated onto fewer pieces of silicon. This is a direct result of the decrease in the size of component transistors. During the early period of video telephone development, the smallest feature on a silicon chip was about 10 microns. Currently, silicon chips are being manufactured with features as small as .3 microns.

Video compression ratios have also improved to increase the rate of image transmission from PicturePhone’s one frame every two seconds to the present state-of-the-art 20 frames per second. By comparison, broadcast television transmits at 30 frames per second.

Now, video telephones have taken two distinct venues. Seemingly, the larger share of the industry was concentrating its efforts in personal computer-based systems, or desktop video teleconferencing technology, which requires computer networks. The smaller effort was aimed at the video phone-through-your-television market which requires no more than a television, a video telephone, and POTS, the industry acronym for plain old telephone service.

The Air Force is testing the latter. According to Col. David L. Rakestraw, director of technology at the Air Force Communications Agency, “because they are so easy to set up and use, video phones are an excellent way for the Air Force to add a video dimension to phone calls home.”

Moreover, the television-based systems cost no more for line transmission than a standard voice call.

Whether consumers on a large scale will finally be attracted to video telephone technology remains to be seen. The technology does seem to have found a niche among those Air Force members who have taken part in the Air Force trials.

After seeing and speaking to his wife in Hawaii from his deployed location in Turkey, SSgt. Lionel Price remarked, “I have been blessed to take part in this.”

Sight Lines - Welcome back, PicturePhone? by Jim Carroll June 1999

This article is Copyright ©1999 Jim Carroll._

It may be freely distributed throughout corporate e-mail systems or other systems via e-mail, or on non-commercial Web sites, as long as this header remains intact. This article may not be reprinted for publication in print or other media without permission of the author, and may not be included in any other fee based paper or electronic publication or distributed in any other form as part of a compilation released for a fee, without the permission of the author. Any other inclusion in a commercial database or other form of electronic access by a commercial organization constitutes theft, fraud and a copyright violation.

Not only that, it’s morally reprehensible!

SIGHT LINES - Welcome back, PicturePhone?

The telephone probably ranks with television and the computer as one of the most significant devices of the 20th century - at least, in terms of its impact on the way we work and play. It’s no surprise, then, that a good many articles have been written to assess the future of this device.

Most of them were remarkably correct - except when it came to one potential use they all predicted.

YESTERDAY

In the 1950s, when computer technology was first being integrated into telephone networks, all kinds of new possibilities were presented to the research scientists at organizations such as Bell Labs and Northern Telecom (formerly known as “Northern Electric” - editor).

Consider the August, 1958, Popular Mechanics article, “Miracles Ahead on Your Telephone.” It suggested that telephones of the future would include “loudspeakers” (speakerphones), the ability to send calls automatically to another number (call forwarding) and a special “talk back” capability to let callers leave a message (voice mail.) The article also envisioned a “robot watchdog” linked to your telephone that would call the police, fire department or other contact should a problem be detected in the home - today’s burglar alarm system.

Such accuracy in prediction was quite typical. In the mid-1950s, when telephones still used the rotary dial, there were widespread reports about the “push-button phone of the future.” There were also many articles– such as the one in Changing Times in May, 1960 (“What’s Happening with the Telephone”) – predicting the day would come when most people would be able to dial telephone numbers anywhere in the world. Keep in mind that this was at a time when many calls, even to someone down the street, had to go through a switchboard operator. The same article also forecast that, one day, businesses would use telephones for “transmitting drawings, blueprints, balance sheets…” (today’s fax machine). It even said that “the ultimate in phones will be the carry-it-with-you instrument” that could be answered from anywhere - the cell phone!

All these articles made one further prediction, and that was the one that gained the most attention - the concept of the videophone. The otherwise-accurate Changing Times piece said a small TV would soon be found in the typical telephone, so that “you won’t have to guess who’s calling - you’ll be able to see for yourself.”

The videophone wasn’t just a concept. Demonstration models were built and gained a huge degree of attention. The 1964 World’s Fair in New York saw the launch of AT&T’s PicturePhone - a device consisting of a telephone handset and a small, matching TV. Suddenly, video telephones were to be real, and accessible to everyone.

That is, anyone with a deep pocket. AT&T first set up the phones in public buildings in New York, Washington and Chicago, charging people $21 (about U.S.$111 in 1999 dollars) to make a three-minute PicturePhone call. Soon, the company began to introduce it into the corporate world. In 1965, BusinessWeek reported on PicturePhone use at Union Carbide, predicting that company executives were “getting a taste of communicating the way the majority of executives may be doing it 10 or 15 years from now.”

At the time, most people seemed to assume that broader use was imminent, and they imagined even more sophisticated devices to come. Science Digest in March, 1965, noted talk of an “ultimate telephone,” the size of a pack of cigarettes, that would carry both voice and video and could be used anywhere. A cell-phone videophone!

TODAY

In fact, the PicturePhone died a quick death soon after its introduction, and video conferencing is still a marginal activity in the corporate world. Technology companies have struggled for years to come up with some type of television-based telephone system but the results, until recently, have been disappointing or very expensive.

The biggest problem is quite simple – global telecommunication systems just haven’t been equipped to handle the huge volumes of data that such technology requires. The August, 1958, issue of Popular Mechanics was bang on when it noted: “one hurdle to practical TV phones is the amount of electronic information necessary for transmitting voice and picture…” To a degree, that hurdle is still with us today.

Yes, you can find video-conferencing equipment in the offices of many major corporations, but it’s costly. Many of those companies have spent upwards of $15,000 to equip their boardrooms with the cameras, audio equipment and high speed telecommunication lines necessary for video conferences. Certainly this technology is not yet widely available to the average citizen.

TOMORROW

Will we ever see the concept of the PicturePhone revived? Two factors suggest that it’s possible.

First, expect technologies that will let us receive huge amounts of data in our home, a necessity for a crystal-clear PicturePhone call. It is said that researchers at Northern Telecom, AT&T and elsewhere have figured out how to send the entire Encyclopedia Britannica from coast to coast in three seconds. That type of telecommunication capability, available to the home at inexpensive rates, would make the PicturePhone a practical reality.

Second, there is constant innovation in Silicon Valley, with companies working on ways for people to use their existing telephones for video conferencing. Take InfoView, a small California firm. They’ve developed a small camera device that sits on top of your television. Plug it into your telephone and TV, and the long-lost promise of the PicturePhone has suddenly reappeared. Dial a friend who also has an Infoview, press a button and the two of you are doing a PicturePhone-type call. The most fascinating thing? The device costs U.S.$399 - a fraction of the cost of any other telephone-based videoconferencing system available to individuals today.

Perhaps the PicturePhone itself will be revived, proving that the concept itself was right - just thirty or so years ahead of its time.

Jim Carroll is the author of the critically acclaimed book, Surviving the Information Age, which addresses issues of coping with technological change. He has co-authored 24 other books which have sold some 650,000 copies, including the national best-selling Canadian Internet Handbook. He can be reached on the Internet at [email protected], and has an on-line site containing many other articles concerning the Internet on the World Wide Web on the Internet at www.jimcarroll.com. He welcomes your comments.

Other Video Telephone Links:

http://www.research.att.com/evergreen/about_us/tech_timeline.html?fbid=Rc4ldr9aZ4Z

AT&T’s Train of Thought web page - 1970 - The Picturephone

http://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/1961-at-t-film-shows-just-how-awkward-videophone-shoppi-1705552144

AT&T’s 1961 AT&T Film Shows Just How Awkward Videophone Shopping Could’ve Been

Tom Jezuit has contributed his personal copy of the special edition, Bell Laboratories “Record” magazine on the Picturephone® for this website! This issue was dated May/June 1969 and gives some great technical and historical information on the Picturephone®. Soon after he sent, we scanned a total of 61 pages, converted the scans into one large PDF file using OmniPro Optical Character Recognition software and Adobe Acrobat to create the PDF file. Over 6 hours were spent scanning and creating the PDF file and proof-reading but no guarantees are made as to its accuracy.

Cover of magazine

To download this Bell Labs “Record” magazine file on the Picturephone®, right click on THIS LINK and choose “Save target as . . . “ A big thanks to Tom for this contribution!

Also, there is a pamphlet on the Picturephone® that you can view by clicking HERE.

Reliable, secure high-speed internet

With CenturyLink Simply Unlimited Internet, you can choose from a wide range of available speeds that fit your online needs. Plus, you can connect several devices with super-fast in-home WiFi.

Order Now